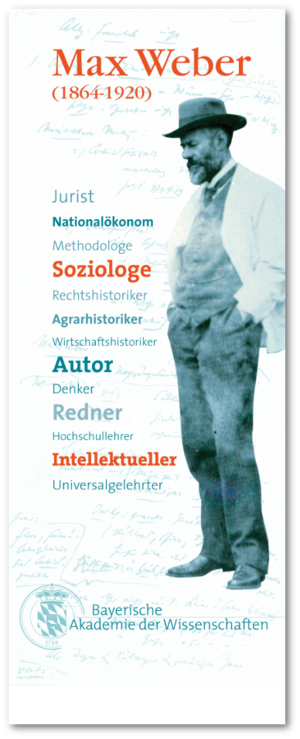

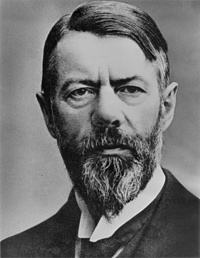

Max Weber – Jurist, National Economist and Sociologist

Max Weber is born in 1864 to a prosperous, educated middle class family with political and economic ties throughout Europe. At the start of his university career, the German Reich was experiencing a period of economic prosperity. Weber studied law, and obtained his doctoral degree and habilitation in Berlin on medieval commercial law and Roman agrarian history. He went on to address the problems of modern agrarian capitalism in the eastern provinces of the German Reich. As a self-declared member of the middle class he fought for a politically self-assured bourgeoisie and against its inclination towards feudalization. He was also an early critic of the sham constitutionalism of the German Reich.

A „Galileo of the Humanities“

(according to Sven Papcke in Die ZEIT from Oct. 5th, 1984, p. 33)

First Heidelberg, then the World

After teaching commercial law in Berlin Max Weber accepted in 1895 an unexpected call to the chair of national economy and finance in Freiburg, even though he had not habilitated in this discipline. Only two years later Max Weber was appointed professor at the chair of national economy and finance in Heidelberg, succeeding Karl Knies. His health deteriorated rapidly, and he was less and less able to comply with his lecturing mandate. In 1903, Weber resigned from his official position, and though still an honorary professor he did not lecture again full time until 1919. For most of his career he pursued the life of a private scholar, concentrating on his economic and political fields of interest.

Back then, leaving the lecture hall with a sense of disappointment,

we thought that Max Weber was ultra conservative. This conclusion, however, proved to be premature.

(In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie (1965): Max Weber und die Soziologie heute. Verhandlungen des fünfzehnten deutschen Soziologentages. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr)

From „Protestant Ethic“ to Universal Rationalization Processes

In 1904/5 Weber published probably his best known work “The Protestant Ethic and the ‘Spirit’ of Capitalism”. It locates the origins of the modern idea of profession in a lifestyle characterized by ascetic Protestantism. To this day this essay is considered one of the most important texts in sociology and economic history.

Around 1911 Max Weber increasingly focused on the economic ethics of different world religions as well as their relation to other social structures and powers. This also enabled him to locate his thesis of a close affinity between the religious and capitalistic spirit within a universal historical framework.

The Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so.

He aimed at developing a typology and sociology of rationalism. Weber diagnosed a rationalizing process characteristic of the Occident, separating Western culture from other cultural areas, leading to cultural phenomena that seemed to be of universal significance and validity. This process has considerably increased mankind’s technical domination of the world in all areas of life but has at the same time also increased the risk of a loss of meaning and freedom.

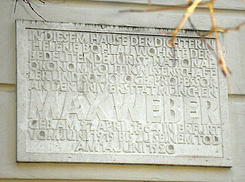

Max Weber in Munich

Here everything – city and people –

is so much 'brighter',

but the weather is awful.

After a trial semester at the University of Vienna, Max Weber again accepted the call to a professorial chair, this time in Munich as a successor to Lujo Brentano. His duties cover lecturing on social sciences, economic history, and national economy. His teaching activity lasted only three semester, since in June 1920 Weber died unexpectedly.

After many short trips and visits his actual stay in Munich finally only lasted just over a year. During this time period, though, revolutionary events were taking place on a daily basis. Nothing less than the reorganization of Germany and Europe is open for debate.

As in Heidelberg so in Munich, Weber frequented intellectual circles. He was a welcome guest in Elsa und Max Bernstein’s literary salon where he met, among others, Thomas Mann. Weber also had contact with Paul Ernst, Ricarda Huch, Rainer Maria Rilke and Helene Böhlau.

Reference: M. Rainer Lepsius' Speech on the occasion of the unveiling of the commemorative plaque, published as: "Max Weber in München", in: Zeitschrift für Soziologie, vol 6., issue 1, Jan. 1977, p. 103–118.

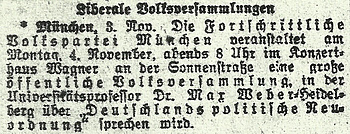

The Munich Speeches

On November 4th, 1918, only a few days before the political upheaval and the end of the German Empire, in the restaurant Wagnersäle in Munich’s Sonnenstraße in front of hundreds of listeners Weber talked about the political reorganization of Germany; Rainer Maria Rilke was in the audience. He argued for the following: voluntary renunciation of the throne by Emperor Wilhelm II, whom he hated, a strong fight against Bolshevism, preparation of a peace treaty acceptable to all participating nations, the parlamentarization of imperial constitution and the abolition of class-restricted suffrage throughout the entire Empire.

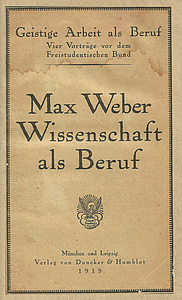

Especially two of his Munich speeches given outside the university and organized by Freistudenten (non-fraternity students) became famous: „Science as a Vocation“ and „Politics as a Vocation“. Weber also proved to be a popular speaker within the university, his rapidly growing audience requiring relocation to the Auditorium Maximum.

Weber... showed himself to be the good, clever and lively speaker that he is.

(In: Tagebücher, Diary entry of Sunday, December 28th, 1919, in: Tagebücher 1918-1921, ed. by Peter de Mendelssohn. Frankfurt a.M.: S. Fischer 1979, p. 352).

Political Statements

Weber with his liberal and partially unconventional political views suffered rejection in Munich’s bourgeois-conservative milieu. In the summer of 1919 he testified in two high treason trials in favor of Ernst Toller and Otto Neurath, both of whom were active in the Räterepublik, the Bavarian republic of councils which sprung up early in 1919 before their suppression in April of that year. He also entered into discussions with communist students. One consequence of this was that Weber was appointed a full member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities by only a narrow margin.

In January 1920 Weber felt compelled to make a political statement. Right-wing students had entered a petition for clemency on behalf of Graf Arco-Valley, who had been sentenced to death for murdering Kurt Eisner, Bavaria’s first Prime Minister; they had also defamed left-wing students for protesting against the petition. Weber declared at the beginning of his lecture that he would have had Arco executed, because now Kurt Eisner would become a revolutionary martyr and Arco a coffeehouse attraction. His next lecture was disrupted by the shouting and whistling of right-extremists, and access to his lectures had to be controlled.

In June 1920, only few months later, Max Weber died in the midst of his two major projects “Economy and Society” and “Collected Essays on the Sociology of Religion”. Both works remained unfinished. Despite this, these are the two works that would mainly establish Weber’s world-wide reputation.

“… and I am familiar with ‘the other shore’,

with its loneliness to all healthy

and next standing persons”